Contested Unity

Published:

Full paper (PDF) — draft in progress; comments welcome at eizadi@sfu.ca.

Imagined communities, then a nagging question

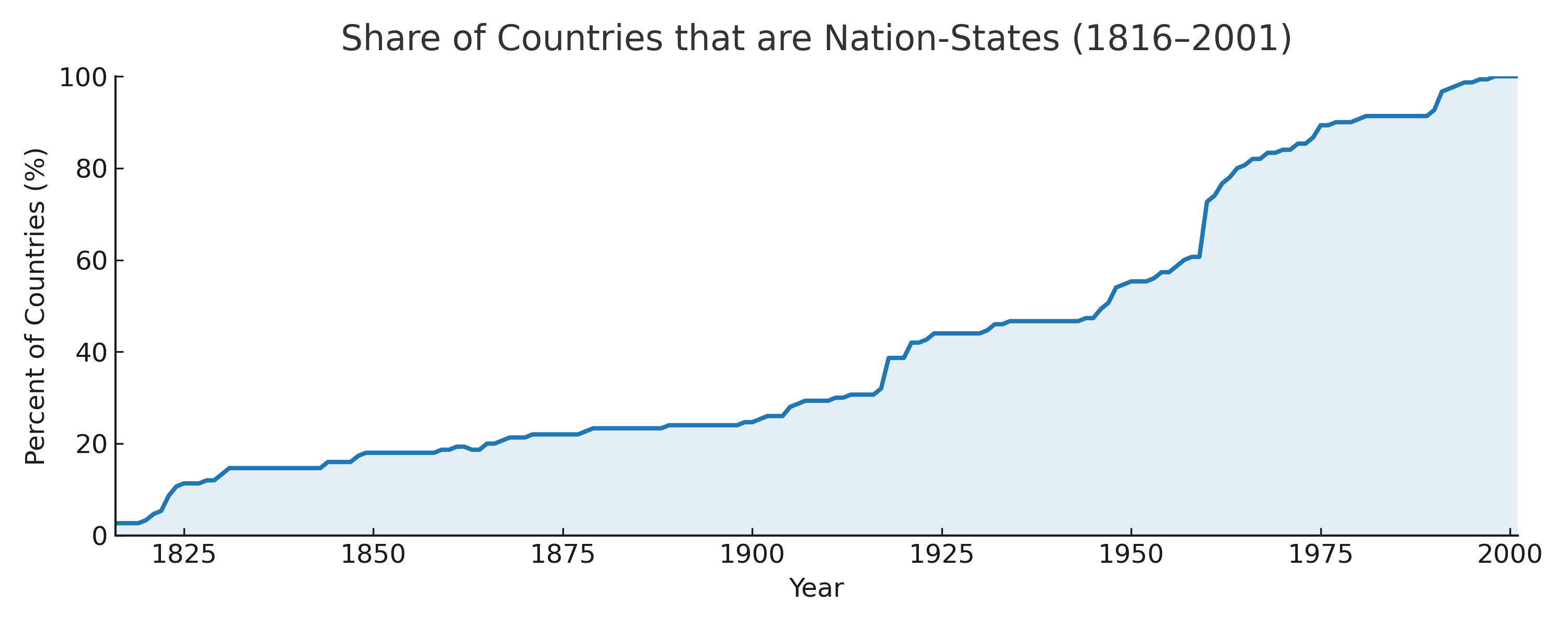

After finishing a paper on the institution of the nation-state (the figure above is created from the data in a related work by Andreas Wimmer), I kept circling the next question: what do we actually mean by national identity—at least in economics?

“Nationalism: an infantile disease. It is the measles of mankind.” — Albert Einstein

That line sticks because the bad reputation is not undeserved. Nationalism can mobilize solidarity—and exclusion. So what do development economists do with this tension? One impulse emphasizes a shared identity for coordination, trust, and state capacity. The other warns that nation-building can crowd out pluralism or backfire.

A tiny taxonomy I find useful

Here’s the organizing thought behind my paper: if we accept a simple chain—

nation-state → nation-building → (a technology of) coordination → national identity,

—then the “technology” is just public policy, and in modern states the main lever is redistribution. In other words, identity formation isn’t mystical; it’s co-produced with the budget choices the state makes.

Concretely, I model a majority allocating a fixed budget each period across:

- a majority-specific good,

- a minority-specific good,

- and a common good (curriculum, shared language, civic programs).

The common good yields some value today and raises the chance of a more civic, integrated polity tomorrow. Identity is the outcome of this repeated bargaining over public goods, not a primitive.

Three regimes, in plain language

Exclusionary. The majority prioritizes itself. No weight on minority welfare or preferences; little to no integration effort.

Split / “multicultural” appeasement. Each group gets its preferred good. The pie is divided, coordination remains costly, and everyone pays for the duplication.

Common-good (civic) regime. The state invests in a not-anyone’s-ideal common good—civic infrastructure that can pave the way for a stronger, more legitimate welfare state later.

The paper’s point isn’t to moralize these categories, but to show when each emerges. Two forces do most of the work: a political trade-off (immediate group benefits vs. deterring conflict and nurturing a civic future), and intertemporal misalignment (today’s citizens undervalue tomorrow’s integration).

This post sketches the intuition. The working paper puts the pieces into a dynamic model and traces the conditions under which polities drift toward exclusion, get stuck split, or converge to civic nationalism.